The wine industry stands as a testament to the fusion of tradition and innovation. At the recent Enartis Stabilisation School, held in October this year, Stellenbosch University lecturer in Agri-innovation and Entrepreneurship at the Faculty of AgriSciences, Dr Albert Strever, explored the implications of the Fifth Industrial Revolution for the wine industry.

The event doubled as the official launch of the new engineering department at Enartis, introducing several smart products and services designed to integrate technology into the wine cellar. Through a new partnership with WineGrid, Enartis now also delivers integrated smart monitoring to the wine value chain.

Integration and innovation

Albert built his academic career in viticulture and research, working on remote sensing and precision technologies in the wine industry, but recently also completed a Masters in Industrial Engineering. This has given him a new perspective on the wider technological context of industry.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) is often described as integrating digital systems with all types of technologies, industries, and applications. But while some technologists believe the world has yet to move past the 4IR, Albert thinks otherwise. “The Fifth Industrial Revolution is not impending; it’s already here,” he says.

Marked by the advent of artificial intelligence, the new era presents both challenges and opportunities for winemaking. The 4IR technology of machine learning, included in the Western Cape’s 4IR report in 2018, has evolved faster than many people expected, and neural networks have now become common in various AI services. “We talk about ubiquitous technology – technology that’s everywhere and changes our lives because they are on our smartphones and in front of us on a normal computer.”

“The disruption is not just coming; it’s here,” he explains. “It’s been especially tangible after COVID, where we got used to an online world. We had to start doing business in a different way.” But even though technology has reached new heights, the real revolution is in how people think and go about things. “It’s a whole different ball game, but it’s also a different mindset. That is what disruption means.”

It’s about more than just Artificial Intelligence, though. “For me, the difference between 4IR and 5IR is ethics,” Albert says. “It’s becoming a question of ‘should we’, rather than ‘can we’.”

Disruption comes from outside

In winemaking, the 5IR could manifest in several ways. “Agriculture doesn’t operate in isolation,” Alberts says. “Our wine industry is in that regard very special since it operates in isolation even less because it’s essentially also a manufacturing industry. Disruption doesn’t always come from the industry we are familiar with.”

Albert advocates for a reconceptualisation of the traditional value chain in winemaking and urges the industry to adopt circular economy principles, focusing on sustainability, efficient resource use, and waste management. “We still see the value chain as linear, but the future value chain of any agricultural industry is not linear. Circular economy, circular agronomy, circular winemaking are all about changing the way we think about energy, carbon, water – everything that goes into the cycle – and how we’re going to recycle and reuse the waste we generate.”

This shift not only addresses environmental concerns but also opens up new business opportunities by finding innovative uses for by-products and reducing costs through efficient systems. “A lot of the innovations we currently look at at the South Africa Wine Innovation Committee have to do with how we can valorize the waste from our processes. That will become the business of the future, to a large extent.”

Ready for 2035

Albert stresses the importance of preparing future winemakers for this reality. Education systems must adapt by incorporating a broader range of skills into the curriculum, including entrepreneurship, adaptability, and lifelong learning. “Let’s make them generalists to make them sink or swim. And experience failure,” he says.

As more technology becomes integrated into the industry, workers will need to update their skills continuously. This shift ensures that they remain relevant and can leverage new tools and practices as they emerge. Albert cites SAAI’s recent launch of a WhatApp chatbot that can assist farmers with their questions in real-time — a tantalising glimpse of the possibilities.

Incorporating AI into everyday practices creates new opportunities for teaching and learning. “I actually encourage students to use AI,” he says. “We need to interrogate this technology, because we know it’s fallible. We know it’s not always trustworthy. But is it my duty to say then don’t use it? No. It’s my duty to say I’m also using it… You want to teach students how to navigate, not the answer, but the way to get the answer.”

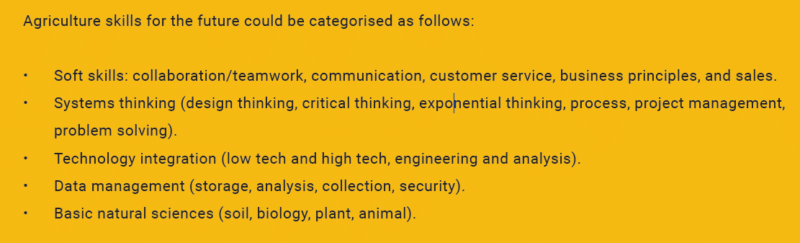

Based on a 2022 report by the Institute for Futures Research (IFR), Albert questions whether students and workers are being adequately prepared for the scenarios it describes. Titled Futures of Agricultural Employment in South Africa 2035 (PDF, 8 Mb), the report identifies the following skills as crucial for a future in agriculture:

Essential future skills. (Futures of Agricultural Employment in South Africa 2035, p. 60)

“I now teach entrepreneurship to students, to have the skillsets not to say ‘it’s not my problem’. Because an entrepreneur cannot do that,” Albert says. “It’s always your problem. Everything you do is your problem. If something doesn’t work and you’re an entrepreneur doing it, it’s your problem.”

“For me, there’s one word: mindset. That’s what the fifth industrial revolution really is. It’s changing the ethics, the political environment in which technology functions, and the social environment in which we function and technology functions. But importantly, if we don’t change our mindset towards how we use technology – it should augment us, not cripple us – and how we teach people to use it, we’re going to fail. And the industry will not go from strength to strength.”